By Kelly April Tyrrell

On Jan. 1, 2020, the Wisconsin Badgers and the Oregon Ducks will storm Pasadena, California, and go head-to-head at Rose Bowl Stadium.

It’s been eight years since the two schools have challenged one another as rivals in a football bowl game, but in the time since, researchers at each public flagship have found ways to collaborate with one another.

For one thing, the University of Wisconsin–Madison and the University of Oregon are teaming up to save the internet.

Research collaborations with Oregon

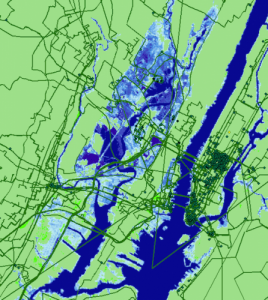

Carol Barford, director of the UW–Madison Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment, and Paul Barford, UW-Madison professor of computer science published a study in 2018 that suggests internet infrastructure may be underwater within the next 15 years as the result of rising seas. Ramakrishnan Durairajan was a UW–Madison graduate student when he participated in the study. Today, he is a UO professor of computer and information science.

By the year 2033, the study reports, more than 4,000 miles of buried fiber optic conduit will be underwater and more than 1,100 traffic hubs will be surrounded by water. The most susceptible U.S. cities are New York, Miami and Seattle, but the effects would not be confined to those areas and would ripple across the internet, potentially disrupting global communications.

“That surprised us,” Paul Barford says. “The expectation was that we’d have 50 years to plan for it. We don’t have 50 years.”

Accelerated learning

A multimillion-dollar project led by UW–Madison’s Justin Williams, professor of biomedical engineering, involves UO biologist David McCormick, along with researchers at other institutions around the country. Funded by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the research is focused on developing methods to stimulate the mechanisms in the human brain that are implicated in learning.

The research, called targeted neuroplasticity training, involves coaxing nerves in the brain to boost their natural learning-associated chemicals and strengthen their connections. The work has implications for military personnel, who are often tasked with learning new skills and copious amounts of critical information within a short period of time, as well as people with learning disabilities and neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.

STEM diversity

UW–Madison, with the Association of Public Land-Grant Universities, is leading a $10 million effort to develop more inclusive and diverse STEM faculty through the National Science Foundation Aspire Alliance. UO is a partner institution in the alliance. The alliance is focused on diversity in hiring, more inclusive teaching, research mentoring and faculty advising and more.

Cell division

The two schools are also working together to better understand the fundamental properties of cellular behavior and cell division. In 2015, UO’s George von Dassow, professor of marine biology, and UW–Madison Professor of Integrative Biology Bill Bement showed that prior to cell division — which is what leads all living organisms to grow, and cancer cells to proliferate — the outside of the cell become “excitable.” This excitability involves important signaling molecules that ultimately play a role in dividing one cell into two.

UW Research helps California

Wisconsin also plays an important scientific role in California. Here are some of the ways:

Vaccines

In 2012, California passed AB-2109, a bill aimed at helping to curb disease outbreaks in the state, such as the measles outbreak at Disneyland in 2014 that led to 131 cases in the U.S. and another 160 in Mexico and Canada. The law requires parents to get the signature of a healthcare professional to opt their children out of vaccines normally required to enroll in school, such as the measles, mumps and rubella shot.

Malia Jones, a UW–Madison scientist in the Applied Population Laboratory, looked at how well the new law worked. Using 15 years of comprehensive vaccination data, her team saw the exemption rate drop from its peak of 3.3 percent of kindergarteners in 2013 to 2.7 percent in each of the following two years after the law took effect.

However, “that statewide rate is misleading, because it’s actually much worse than that,” says Jones, who explains that the clustering rate — the probability that an exempted student will encounter another exempted student in their school — dropped only slightly, from 16 percent to 15 percent.

Dissatisfied with these outcomes, in the wake of the Disneyland outbreak, California passed SB-277, which eliminated all non-medical exemptions. Exemption rates have since gone down substantially.

Owls

In 2017, forest and wildlife ecology professor Zach Peery and his graduate student Gavin Jones looked back at the results of a 1992 change to logging activity in national forests intended to help protect habitat for California’s spotted owls and bring the bird’s numbers back up.

They found the owls were paying down an “extinction debt” after years of population declines but that stabilizing and even increasing spotted owl numbers might require more than just halting habitat loss. It likely requires restoring to the landscape the large, ancient trees they rely on. And patience.

Wildfires

California’s rapidly changing wildfire patterns have drawn UW–Madison ecologists studying the encroachment of developed land.

The wildland-urban interface has increased rapidly since 1990, according to research led by forest and wildlife ecology professor Volker Radeloff, adding an area roughly the size of the state of Washington in just two decades. Nearly all that growth from 1990 to 2010 was attributable to homebuilding, putting people’s bedrooms in formerly sparsely settled areas and increasing the spread of invasive species, pollution, animal disease —and human-ignited wildfires.

“We’ve seen that many wildfires are caused by people living in close proximity to forests and wildlands. And that when these fires are spreading, they are much harder to fight when people are living there, because lives are at risk, because properties have to be protected,” says Radeloff, who chronicled an increase from 31 million homes in the wildland-urban interface to more than 43 million.

Vegetation management, appropriate building materials and zoning regulations informed by wildfire risk can help mitigate the sort of dangers to people and ecosystems repeatedly threatening Californians.

“There’s a lot that can be done,” says Radeloff. “And I think what our data shows on the development side, and others have shown on the climate change side, we better start doing it or otherwise we will have news like [life and property loss in California] again and again.”

Health care marketplace

California’s big insurance market makes for a useful window into the impact of the federal Affordable Care Act on healthcare coverage and service.

David Weimer, a professor in UW–Madison’s La Follette School of Public Affairs, led a comparison of private commercial coverage available to Californians and coverage obtained through the state insurance marketplace or exchange, called Covered California.

Covered California customers had in-plan access to fewer hospitals — 83 percent as many — as buyers of commercial health plans. But the relative distance to their respective hospitals was similar for the two groups, as was the care available at those hospitals.

“Indeed, our analyses paint a somewhat surprising picture of the difference in the average quality of hospitals in these networks,” Weimer says. “Two of the analyses show no substantive difference in the average quality of the networks, but a third measure indicates that the average quality in the exchange networks is actually higher than that in the commercial networks. Insurers may be deliberately excluding some hospitals that have not been designated as top performers.”

Urban wildlife

David Drake, a UW–Madison professor of forest and wildlife biology and wildlife extension specialist, has weighed in on California’s troublesome urban coyote situation. According to the LA Times, there are somewhere between 250,000 and 750,000 coyotes across California, and the canids are well-adapted to urban settings. At least 49 people have been bitten by coyotes in Los Angeles County since 2011, more than half of them in the same area near downtown.

“More people are bitten by coyotes in Southern California than anywhere else — it’s a phenomenon unique to that region,” Drake recently told the LA Times. “No one knows why this is happening, exactly. But you just don’t see that in other parts of the country.”

When it comes to badgers, Wisconsin, California and Oregon all have them, Drake says. One particular subspecies is found in both Oregon and California, but not in Wisconsin. However, “badgers are known to eat ducks and their eggs,” he says. “Badgers would definitely dominate a duck! Go Badgers!”